Let’s start with a little background:

Let’s start with a little background:

YouTuber Vintage SF has been posting excellent reviews of older science fiction works—nearly all from the 20th Century, and most of those published after 1950. He’s also been posting episodes—a sort of sub-genre, I guess you’d say—focused on books published during a particular year. This sounded intriguing, and I thought I’d try it as a way to prompt myself to read some books I’ve not read. I haven’t really avoided these books, but I can’t say that I’ve made a definite effort to hunt ’em down and read ’em all the way through.

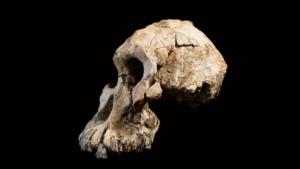

So I picked 1959. A year on the cusp of a decade of revolution and transformation. Hawaii and Alaska were admitted as full-fledged states to the U.S., and Alaska supplanted Texas as the largest state—at more than 660,000 square miles, it’s more than twice the size of the Lone Star State. Fidel Castro took control of the Cuban government as premier after the island’s revolution. The Soviet Union launched Luna 1, intended to orbit the moon, but a control error made it the first man-made object to orbit the sun instead. NASA named the Mercury Seven pilots. The Saint Lawrence Seaway was completed and opened to shipping between the Atlantic Ocean and the Great Lakes. China invaded Tibet, and the Dalai Lama and thousands of Tibetans fled to India. Two monkeys were the first living creatures to survive a space flight; they were launched 300 miles into space in the nosecone of a Jupiter missile. Louis and Mary Leakey discovered the first Australopithecus skull. Singer Billie Holiday died. NASA’s Explorer 6 satellite took the first picture of Earth from orbit. Luna 2 crashed on the moon—the first man-made object to reach the surface. Luna 3 took the first photos of the moon’s far side. The prototype of the defibrillator restored a patient’s heart rhythm using 400 volts of electricity. Twelve countries signed the Antarctic Treaty, setting aside the southernmost continent as a scientific research preserve and banning military activity there.

Exciting stuff!

To be honest, I have to admit I have avoided reading SF from this era—passively if not purposefully. It’s a year in that post-war period between what’s considered the SF Golden Age and the full-blown SF New Wave. My impress

ion of this stretch of science fiction—and I don’t claim that it’s an informed opinion—is that it mostly goes through the motions (there are spaceships and aliens and rayguns) hanging on from the Golden Age, but hadn’t quite found its footing or a definite path for where to go next. What I’ve read so far has felt a bit ho-hum.

As I go on this journey, maybe my opinion will change. I hope so, because one doesn’t begin a journey to end up in the same place one starts.

So: 1959.

I started with the Hugo-winning novel for that year, Robert A. Heinlein’s Starship Troopers. Most people have probably heard of it because of the 1997 film by Paul Verhoeven. (And I had no idea until just now that this movie had four sequels. Four! Really, Hollywood?) Not an entirely faithful adaption of Heinlein’s novel, the film is more satire of what it considers the military mentality. The book, as Vintage SF describes it, “is a novel about training and ideology.” That’s an accurate assessment.

If you want lots of military SF battle scenes, check out the movie. If you want fewer battles and lots of background about military culture, go for the novel.

The story has a first-person narrator, Juan “Johnnie” Rico. We see him as a civilian, then as a recruit, and as a trainee in boot camp through a long portion of the book. If you’ve read any of the rash of acclaimed novels that came out about the Vietnam War-era Army, particularly Gustav Hasford’s The Short-Timers, Kent Anderson’s Sympathy for the Devil, or even War Year by Joe Haldeman (who wrote another Hugo-winning novel about the military in space: The Forever War), you’ve read far tougher stuff than what Heinlein presents in Starship Troopers.

The story has a first-person narrator, Juan “Johnnie” Rico. We see him as a civilian, then as a recruit, and as a trainee in boot camp through a long portion of the book. If you’ve read any of the rash of acclaimed novels that came out about the Vietnam War-era Army, particularly Gustav Hasford’s The Short-Timers, Kent Anderson’s Sympathy for the Devil, or even War Year by Joe Haldeman (who wrote another Hugo-winning novel about the military in space: The Forever War), you’ve read far tougher stuff than what Heinlein presents in Starship Troopers.

But Heinlein was writing in a different time and, even though Starship Troopers is set in the future, he’s really writing about a different sort of war than what the Vietnam War became. Training in Starship Troopers looks and feels—with some slight material differences—like it takes place in a World War Two setting.

But Heinlein was writing in a different time and, even though Starship Troopers is set in the future, he’s really writing about a different sort of war than what the Vietnam War became. Training in Starship Troopers looks and feels—with some slight material differences—like it takes place in a World War Two setting.

This is part of what has been to me a barrier to this era’s SF—much of it feels like its world-building is based on a look outside the living room picture window, then some space suits, spaceships and rayguns are thrown in by the prop master to set a scene. The vast reaches of outer space are just suburbs of the major metropolitan area of Earth.

Maybe I’m expecting too much.

For its time, Heinlein’s approach in Starship Troopers was new to SF. That’s hard to imagine now, when perhaps half of a year’s SF publishing output may be categorized as military SF. But a lot of today’s military SF writers look to the template Heinlein forged in Starship Troopers.

And those expansive sections on training would’ve been familiar to military vets who served in the war, as Heinlein did. What seems dated in some measure today was new in 1959.

But part of Heinlein’s mission in writing this book was to challenge readers’ notions of citizenship and—as a part of responsible citizenship—service. The book’s proposition that only those who serve in the military should have full voting rights is a controversial one in our world. One wonders what those who weren’t in the military during WW Two—but who served on the Home Front, keeping industry and farms going—might have thought about the book’s message.

I don’t know much about Heinlein, but I wonder if he liked stirring up folks to make them think and complain. I suspect he may have sometimes used that wonderful line spoken by J. Wellington Wimpy (aka Wimpy) to Popeye to drum up some action: “Let’s you and him fight.”

Before its book publication, Starship Troopers was serialized in two issues of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (the October and November, 1959, issues). I’d like to read the letter columns in the subsequent issues to see what readers thought of this novel and its assertion about citizenship. I’m sure the story and its details generated some lively debate at the time.

Before its book publication, Starship Troopers was serialized in two issues of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (the October and November, 1959, issues). I’d like to read the letter columns in the subsequent issues to see what readers thought of this novel and its assertion about citizenship. I’m sure the story and its details generated some lively debate at the time.

So: Hugo winner, meaning Starship Troopers was considered by SF readers to be the best novel of the year. I’ll say it’s simultaneously engaging and offputting, breaking some rules for fulfilling readers’ expectations and laying a table with food for thought and debate. It certainly gets high marks for influencing many novels and stories that have followed.

I’ll have to read more from 1959 so I can have a truly informed opinion before I can give my final verdict on Starship Troopers. Keep a look out for future posts about 1959 SF.